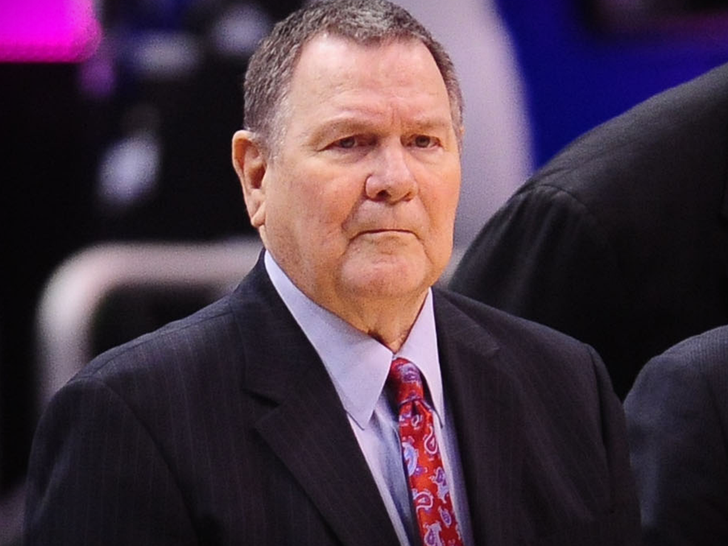

An excerpt from “Prehistoric: The Audacious and Improbable Origin Story of the Toronto Raptors,” highlights Brendan Malone’s journey as the first head coach.

Alex Wong is a freelance writer, radio host and author of three books. This excerpt, from his latest book “Prehistoric: The Audacious and Improbable Origin Story of the Toronto Raptors” focuses on former Raptors head coach Brendan Malone, who died earlier this month at the age of 81. It was compiled from two separate chapters.

Brendan Malone was eager to get started at his new job with the Raptors, but just three days after the NBA Draft took place at the SkyDome, the basketball world came to a stop after owners and players failed to reach a new collective bargaining agreement. A lockout started on July 1, and the start of the Raptors’ first season was suddenly in jeopardy. As he waited for the two sides to come to an agreement, Malone woke up every day with a nervous energy. He would keep busy by watching tapes of old NBA games and going for a round of golf in the afternoon, but the coaching lifer just wanted to get back to work.

Malone grew up in the Astoria-Queens neighbourhood of New York. The son of Irish immigrant parents, he watched his dad unload railway boxcars while his mom worked as a nanny. From an early age, Malone was instilled with an appreciation for hard work. His family didn’t own a bike or a car, so Malone spent most of his childhood hanging out at the playground across the street from his tenement building. He was the tough kid in the neighbourhood, getting into fist fights and winning the respect of his peers. Malone lived a simple life with his parents and three siblings. “We made the best of what we had,” he recalls. “We didn’t even know what we were missing. We were happy, and I liked all the kids in my neighbourhood.”

At 13, he made the pee-wee hockey team and spent every Sunday afternoon playing at Madison Square Garden during the intermissions of New York Rangers games. Malone travelled across North America, including his first trip to Canada, where he competed in a tournament in Halifax, N.S. After starring as a forward in a metro hockey league at 16, Malone gave up his dreams of playing professional hockey and turned his attention to basketball. After riding the bench in his senior year at Rice High School in Harlem and playing briefly at Iona College, Malone realized he wasn’t going to make the NBA, so he joined the Army before returning home and landing a job as a writer with the New York Daily Mirror while working with the police service at the Empire State Building. “I didn’t have any direction. I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” he says. “I was a log just drifting down the river.”

Everything would change after Malone got his master’s degree in physical education at NYU. He reached out to Robert McMullen, the principal at Power Memorial Academy, an all-boys Catholic school in New York. The school had become a basketball powerhouse thanks to a high schooler named Lew Alcindor, who earned the nickname “The Tower from Power,” while leading the school to a 71-game winning streak and three straight New York City Catholic championships. Malone was hired as the director of physical education and coached the school’s basketball team for a decade, leading them to two state championships. “It was my most satisfying time as a coach,” Malone said of his time at Power. “You were with the kids all the time and helped them get scholarships. You could become their surrogate father. Helping other people achieve success is what makes me happy.”

Malone was a three-time New York high school coach of the year, and college programs had started to pay attention. In 1976, he accepted an offer to become the assistant coach at Fordham and later moved to Yale before spending six years at Syracuse. Malone got his first college head coaching job in 1984 with Rhode Island and was hired by the New York Knicks two years later, joining Hubie Brown’s coaching staff as an assistant. After Isiah Thomas and the Detroit Pistons lost in seven games to the Los Angeles Lakers in the 1988 NBA Finals, assistant coach Ron Rothstein was hired by the Miami Heat to be their head coach. Chuck Daly called Malone, who joined the Pistons as an assistant coach.

After winning two championships with the team and developing a reputation as a defensive mastermind, Malone was now looking to import the same identity he built in Detroit to an expansion franchise in Toronto in his first opportunity as an NBA head coach after 27 years of coaching. He would finally be able to get back to work when the lockout ended in September. The two sides reached a six-year agreement which would include a significant increase in the salary cap and average player salary over the term of the deal. When the league opened for business again, the Raptors announced they had traded B.J. Armstrong to Golden State for Victor Alexander, Carlos Rogers, Dwayne Whitfield, Martin Lewis and Michael McDonald. (The trade had been agreed upon before the lockout but was now official.)

Training camp would start in October at Copps Coliseum in Hamilton. Malone had a month before opening night to find a roster capable of competing during the franchise’s first season. “We have never been together before, and it takes time to build up team chemistry,” he told reporters. “I want guys who’ll show up in boxing gloves, who’ll kick butt. I don’t like soft players with finesse.”

The expansion agreement allowed the Raptors to invite up to 30 players to camp, higher than the 20 players permitted to other teams. On the eve of training camp, Damon Stoudamire flew to Toronto and signed his first NBA contract, a three-year, $4.6 million (U.S.) deal, before hopping on a bus to Hamilton. It did not take long for the rookie to recognize Malone was an old-school, no-nonsense head coach who wanted to establish a blue-collar, defence-first identity for the expansion franchise.

On day one, the team started a two-a-day practice schedule which would become the norm during camp. “It was so tiring,” Stoudamire recalls. “We practiced for like three hours twice a day for two weeks straight. It was a different grind, man. My body was struggling to recover. I never did anything after practice. I just went straight to my room to get my body right.”

Players started complaining to reporters on the second day. When Malone was made aware of the complaints, the head coach snapped. “This is a tryout camp,” he said. “If you don’t think you can practice twice a day, you don’t belong on this team.” Malone had granted a one-on-one interview with the Toronto Star during the lockout and explained his lack of tolerance for laziness. “Some guys are paid a lot of money who don’t play hard all the time,” he said. “Teams should make a thorough background check of players they draft, to see what makes them tick.” After a week in training camp, Malone made it clear there weren’t enough players meeting his standards. “I see a lot of good things and a lot of bad things,” he told reporters. “There are times I walk out depressed and other times I walk out happy.”

During the first season, Malone stayed at the Westin Harbour Castle Hotel, his stay arranged in exchange for season tickets provided by the team to the hotel manager. “I loved Toronto,” he says. “I could walk up Yonge Street all the way to St. Michael’s Hospital and check out all the different neighbourhoods in the city.” Malone would run into Raptors fans on his long walks during the season, who would compliment him on how hard the team was trying. It would lift the head coach’s spirit during the losing streaks, even if it were just for a brief moment.

After every win, Malone usually got a call from assistant general manager Glen Grunwald. He was passing on a message from general manager Isiah Thomas, who wanted the head coach to manage Stoudamire’s minutes and give the other young players some more rope. The Raptors wanted to see what they had on the roster. “The strategy was not to win as many games as possible,” Grunwald says. “Brendan was a very good coach, but he was single-minded and focused on winning games. Isiah didn’t want to do too well because he wanted to get a good draft pick. We had to make sure we weren’t too good too soon so we could build through the draft.”

The idea of not trying to win every game was blasphemous to Malone. How could you build a team’s identity of hard work and defence and ask the players to compete for 48 minutes without trying to win?

“Coaches coach to win. We don’t coach to lose,” Malone says. “I remember driving to the SkyDome for a game and seeing a man holding his son’s hand. They were going to the game. I sat there and thought, ‘We’re cheating these people by not trying to win a game. We’re cheating the players on the team.’”

The phone calls would keep coming after games, but Malone kept coaching to win. He kept Stoudamire on the court for entire games. He relied on his veterans and kept the players he didn’t trust on the bench.

He was going to try and win every game.

From PREHISTORIC: The Audacious and Improbable Origin Story of the Toronto Raptors, published by Triumph Books. Copyright © Alex Wong, 2023. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.